More on ‘New Learning and New Ignorance’

C. S. Lewis is the great debunker of shallow modern

thinking. It’s amazing how much the myth of progress, which reigned in his

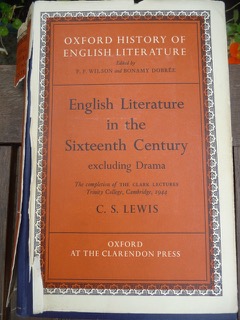

days, is still with us. So it’s refreshing to read what he writes (in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century) about

Renaissance thought.

Two things, he tells us, that were ‘reborn’ in the

Renaissance are things that modern thinking consigns to a ‘medieval’ dustbin:

astrology and magic. It might surprise some people to learn that these two

practices underwent a new and more ‘scientific’ development in the fifteenth

and sixteenth centuries. Even more surprising: these two systems, which you

might expect, as ‘superstitions’, to be arm-in-arm, were actually at daggers

drawn. How come? Lewis explains: the magician asserts human omnipotence; he

believes that, if he can find the key, he can control Nature. The astrologer

asserts human impotence; he is a determinist, believing that everything humans

do is controlled by natural powers far beyond their control.

Lewis says that, separate from witchcraft, there arose

another, quite respectable kind of magic in the Renaissance, sometimes called

‘high magic’. In medieval literature there is plenty of magic—such as is

practised by Merlin, King Arthur’s wizard, for example. But magic in medieval

stories is unmistakably fairy-tale magic. In fact ‘magic’ is the earliest

meaning of faerie in medieval

English—it’s ‘fay-ery’, what ‘fays’ do, rather than what real-world people do.

It ‘could rouse a practical or quasi-scientific interest in no reader’s mind’,

says Lewis. But when you come to the Renaissance, things are different. Magic

is portrayed as something that ‘might be going on in the next street’.

‘Shakespeare’s audience,’ (Lewis again) ‘believed that magicians not very

unlike Prospero’ (in The Tempest) ‘might exist.’

High magic can be studied in the works of European writers

from the mid fifteenth century onwards, even in Henry More’s Philosophical

Works (1662); the supposed ‘medieval

survival’ outlived all the other achievements of the Elizabethans. And actually

its exponents, in common with the other humanists of the period, had contempt

for the ‘middle ages’. They regarded themselves as reviving learning that had

been lost during that ignorant period. It had been forbidden and denounced by the

Church right from the start; unjustly, because it is a ‘high holy learning’.

Why is it ‘high’? Because it held that ‘there are many potent spirits besides

the angels and devils of Christianity’.

Lewis goes on to show (and I have no space to summarize it)

that this Renaissance magic was based on a very widespread and well-established

‘Platonic theology’. And, he says, the new magic is no anomaly but ‘falls into

its place among the other dreams

of power which then haunted the European mind’. Francis Bacon, the pioneer of

the new science, has much in common with the magicians. Both seek knowledge for

the sake of power and both dream of a time when Man will be able to perform

‘all things possible’. And indeed Bacon thought that the aim of the magicians

was ‘noble’. The major difference is that science succeeded and magic

failed—but at the time they didn’t know that this would happen.

What then did the astrologer and the magician have in

common? Lewis says: ‘both have abandoned an earlier doctrine of Man’. The

medieval doctrine guaranteed humans, in their place on the hierarchy of being,

their own limited freedom and efficacy. But now both became uncertain: ‘perhaps

Man can do everything, perhaps he can do nothing.’

Well I am still finding that fascinating. I loved the way Lewis cuts in between all the different ideas which flew around in the Renaissance intellectual culture, and demonstrates how each relates to the others. So interesting, especially in view of later developments too -

ReplyDeleteThis is so interesting. I'm teaching The Tempest at the moment and we've done some work on John Dee and magic. What you've written here would really help to clarify. Would I be able to use it? Would you mind?

ReplyDeletePlease help yourself! Every word of it is borrowed (well or badly) from C. S. Lewis. He mentions Dr Dee in this chapter of ELSC. Thank you for being interested.

Delete