Writing about writing about writing about writing

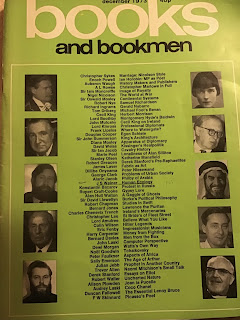

Back in the 1970s, my dad used to contribute short reviews of popular science books to a monthly literary magazine. Looking through those copies of this magazine, which I still have, is like going back into a forgotten world. The magazine was called books and bookmen (they always wrote it with lower-case initials). Bookmen! Such a title would be impossible today. And indeed, men were the main contributors. In the December 1973 issue, for example, of the 45 authors of articles listed on the title page, 3 were women. 6%! And this was matched by expressions and attitudes. For example, a certain Audrey Williamson complains in a letter to the editor that ‘Prof. Rowse assumes I cannot read’. The magazine prints A. L. Rowse’s rejoinder: ‘I did not say that the lady cannot read; I said, she was in no position to judge.’ The lady! But then Rowse was born in 1903.

books and bookmen was highly regarded, and the contributors included some of the most famous people of the time: not only writers, but politicians, explorers, scientists, and so on. A monthly issue was a guide to most of the books that had just been published, so that a reader would gain a good idea of what new books would interest them. An issue cost 40p in December 1973 — I believe this is £4.25 in today’s money. For that you got between 40 and 50 substantial articles and between 30 and 40 shorter (though by no means brief) ones. You got about 100 pages, which works out to be at least 120,000 words of reading.

The more in-depth reviews were often a great deal more than a discussion of a newly published book. The author might well be an expert on the topic; they may, for example have known the person who was the subject of a biography or have been present at an event described in a study of politics or warfare. Sometimes this was an opportunity for pontification, pomposity, or self-glorification, of course. Egos were often on display. But in fact the magazine constituted a very tolerant forum. The spectrum of contributors ranged from far right to far left, from atheists to clergy. And of course since many of the contributors were also book writers, they frequently reviewed each others’ works, and did not hold back if they disagreed.

I’ve been reading these ancient magazines with enthusiasm. There’s so much to learn. Let me pick at random from a review of a critical study of the eighteenth century novelist Samuel Richardson. Like me, you may have read his epistolary novel Pamela and been struck by what a funny way it was to write a novel, but also like me, you may not know that this was the origin of the novel as we know it. More than that, it arose almost by accident. Pamela is supposed to have originated ‘in a proposal by the printers that Richardson should write a collection of model letters for the edification of persons unaccustomed to correspondence’. Another random item: the author of the critical study is quoted as saying that Richardson

places his characters in a situation of conflict, and the fiction grows, not through his complicated plotting and design, but by imagining how those characters will react to that moment, and so create the next, and the next.

Isn’t this an interesting way of building a novel?

As I have mentioned, the book reviewed was a study of the works of the author Richardson; the author of the study was Mark Kinkead-Weekes (1931–2011), an academic at the University of Kent, who by all accounts was quite distinguished; the author of the review of Kinkead-Weekes’s book was Robert Nye (1939–2016), a poet, novelist, and children’s writer; and I am writing about his review: so, to be trivial for a moment, I am writing about writing about writing about writing (this should satisfy the stringent requirements of this blog and perhaps compensate for my past lapses).

Have you ever heard of Mark Kinkead-Weekes, for all his great critical studies of Richardson, Lawrence, and Golding? Have you heard of Robert Nye? Just possibly. What about some of the other contributors to December 1973’s issue: Auberon Waugh, Oswald Mosley (yes, the ex-leader of the British Fascists), Nigel Nicolson, Colin Wilson, Enoch Powell, Richard Ingrams? All dazzlingly famous in their day. What about Ian Moncreiffe, Christopher Sykes, Cecil King, Tom Driberg? Also members of the Great and the Good, but now gradually being forgotten. It is quite sad to think that leading writers are mostly forgotten after forty years.

And, in a way, even sadder, is that many outstanding books of that time are also now forgotten. Books that sound wonderful when you read the descriptions in this magazine, books about subjects you would just love to read about, books that are lauded to the skies. As well, of course, as books which were obviously very poor and deserved their immediate obscurity.

But it gives one a sobering perspective on our own writing. All that hard work we do: readers may love the result, for a while. But after a few years it, and we, will be forgotten. In view of this, what sort of writers should we be? Well, I’d say, seeing that we have only a limited opportunity, we should give it our very best shot. The best production and printing, naturally. Also the best possible editing. The finest style we can manage. And an inner theme that is worthy of our high calling.

Reading your blogpost, thoughts of my father came to mind. It seems there used to be excellent, in-depth reviews in newspapers. It seems we, as people, took time to read writing that required thought and marination. Now we are SO busy in this tweet-level of life. Perhaps lockdowns will gather us back, or up! Thank you for this thoughtful blogpost, so well written and inspiring me to take a step back in time for some great writing. I only know about one of the writers you mention (Nye), though we were required to read Pamela in college.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your appreciation!

DeleteSo agree with Kathleen (above): I would like to see more 'objective' and 'critical' intelligent in-depth reviews, surely we as a nation/a culture/a society are not incapable? Not being a linguist (at all), I don't know if these appear in the newspapers/magazines in Europe - though I suspect they do/might. The main lack in the Books & Bookman magazine was writing by women! But that will have changed by now - or should have had every reason to... To be critical in a review is not to "rubbish it', it to investigate it thoughtfully for the good and the less good, to think about the work, and when people only say they 'love/hate', or only congratulate, what can we learn, and how authentic is our writing? Thoughts to ponder!

ReplyDeleteBooks and Bookmen! Everything was "men" in the 1970s as I recall. I've heard of most of them, but that's only because I'm such a nerd. Tom Driberg was a busy lad - he started the William Hickey column, wrote, taught and had a very lively private life. As well as being a Soviet spy (probably). But you're right, he's not read today and yet in his time, a very famous person.

ReplyDeleteThis was fascinating. Thank you

ReplyDeleteFascinating and challenging post. But please, can I make an appeal to all writers for this blog to add your name to the title? I get the posts by email and the signature does not appear there, so I have to go online to know who it's by. Wendy asked us when it started to put our name in the title, it's very frustrating when people don't!

ReplyDelete