Writing With a 'Message' in Fiction

There

is an ongoing debate in Christian writing circles about how appropriate it is

to consciously have a ‘message’ to communicate through fictional stories. Some

writers of overtly Christian Fiction readily admit they write in order to share

God’s love and to hopefully lead readers to salvation. Then there are writers

of Christian Fiction who want to write stories for other Christians that

reflect Biblical values and standards that aren’t found in ‘secular’ novels.

Further along

the spectrum are authors like me* who prefer to describe ourselves as writing

general fiction from a ‘Christian worldview,’ where themes of forgiveness and

redemption are subtly woven into the plot but are never the main point of the

story, and the thought of proselytizing our readers is not something we are

comfortable with. Then there are writers who are Christians who write

completely secular novels and their lives – not their books – are their

witness. (*This relates to my adult books. My children’s books are stories from

the Bible so by definition overtly Christian).

The question I’d like to ask is: is

it wrong to start writing a book with a conscious message in mind?

A few months ago I spent a lovely weekend at the Harrogate Crime Writing Festival, listening to ‘big name’ crime authors being interviewed. I was struck by how many of them had no qualms in saying they were trying to say this or that through their books. Others said they hadn’t decided on what their next book would be, not because they didn’t have an idea for a plot, but because they didn’t yet have ‘anything to say’ through it.

A panel of authors who wrote legal

thrillers – all of them former lawyers – were unanimous that they wrote novels

because they wanted to say something about injustice or the failings of the

criminal justice system. None of them seemed to get their knickers in a knot

about whether or not it was ‘right’ to have a message in their books.

In addition, those of us who studied

English Literature at school or university will remember writing essays on ‘themes’

and asking the question ‘what is the author trying to say?’ There is a reason

love stories like Jane Eyre are set works for academic study whereas

Mills & Boon novels are not – the former are trying to say something about

society or the human condition and the latter generally are not trying to say

much beyond: finding someone to love and love you back makes your life better.

This does not mean Mills & Boon novels don’t perform a function and that

it’s wrong to enjoy them, but there would not be much scope to write an A Level

paper on the deeper meaning of one of them. So, hopefully you accept my point

that many books DO have messages and themes consciously written into them and

that it is perfectly acceptable to do so.

The question I believe is not

whether we SHOULD have a message, but if we do, how do we weave it into the

narrative? I would like to suggest three things:

- Story

first, message second. The story must always be fore-grounded. Allow

the story to entertain and be true to itself. If the message gets in the

way of the story, chuck it out or find a more subtle way to tell it.

- Don’t

have your characters ‘telling’ the reader what the message of the book is in

dialogue or internal monologue. Allow their actions to ‘live out’ the

message.

- Don’t

write ‘on the nose’. When I did my MA in Creative Writing 12 years ago, my tutor was an

atheist. My final submission was a theatre play. The play wasn’t

‘Christian’ but it did have spiritual themes and it helped me no end when

my tutor wrote ‘OTN’ in the margin. He meant ‘on the nose’ and he did so

when he felt I was being too preachy or overt in the ‘message’ of the

play. With his help I eventually got a distinction.

So now, with anything I write, I always ask myself:

is this too OTN? Or better still I ask my editor or a non-Christian friend to

read it and tell me if they think I’ve laid it on too thick. What tips do you

have about not writing too ‘on the nose’? Feel free to add them to the comments

section below.

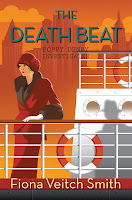

Fiona Veitch Smith is a

writer and writing tutor, based in Newcastle upon Tyne .. Her mystery novel The Jazz Files,

the first in the Poppy Denby Investigates Series (Lion Fiction) was shortlisted

for the CWA Historical Dagger award in 2016. The second book, The

Kill Fee was a finalist for the Foreword Review

mystery novel of the year 2016/17, and the third, The

Death Beat, is out now. Her novel Pilate’s Daughter a historical love story set in Roman

Palestine, is published by Endeavour Press and her coming-of-age literary

thriller about apartheid South Africa

Interesting. The idea of a 'message' is difficult to define: obviously Austen et al had one - a wry look at society. How useful to experience a group of writers discussing the subject from a point of view other than religious! There is room for that. And, can we expect the average totally secular person today to recognise a theme of redemption? Can we ever set the record straight on Christians not all being fundamentalists with the classic list of 'don'ts'? Something I try to address, and never ever meaning to 'preach' which looks like 101 - other faiths manage it - good question whether we can. or whether the image of 'Christians' is too tarnished by certain, and various, groups. There cd be a whole discussion here, done objectively, and without the words 'preachy' or 'message'!

ReplyDeletePoint taken about Christians tending to agonise about this more than other faith groups - hence this post! However I think the words preachy and message are perfectly appropriate. We don't want to be preachy but sometimes we can be. And re message that's not necessarily a negative. As I said the crime writers were happy to talk about the underlying message, aka the thing they hoped to say through their books.

DeleteI think having a non-Christian reader is a good idea. My mentor isn't Christian and although my book isn't Christian, my characters are inspired by their faith and do pray, forgive people and consult priests. She hasn't had any issues with this aspect of the book and I have actually been able to discuss my faith with her in quite a natural way. I believe the writing looks different for different people but if we draw close to God, what we know of Him can't help but come out.

ReplyDeleteGreat that you have that relationship with your writing mentor, Rebecca. It looks like it's bearing fruit.

DeleteI think that what we really believe in will show itself in our writing, unless we make deliberate attempts to hide it, and perhaps not even then. Much as it does in the rest of our lives, perhaps. I think that Tolkien once said something like 'I am a Christian, and that will naturally show in my writing'. I can't find the exact quote, but that's certainly what I hope will happen with my writing.

ReplyDeleteI agree Paul. It should be natural. Sometimes it doesn't come across as natural though. I was hoping to explore ways to enhance or enable that natural 'showing'.

DeleteForgive me, but I think the question of whether a 'message' has its place in a novel might be confusing to some. Does it, perhaps, convey the idea of a 'sermon'? You've spoken elsewhere about being 'preachy'. But the fact is that 'theme' is an essential to any plot. Without 'theme' a story is empty; frivolous.

ReplyDeleteIn the days when I was commissioned to write biography / testimony by Hodder & Stoughton, even here, in non-fiction, the issue of theme was one that had to be addressed. In writing the story of one lady's healing, I had to remind her, frequently, that some of the incidents she would have liked to have included were, in fact, irrelevant. Hard! For her to understand. And for me to have to tell her. But my editor would not have accepted it otherwise.

Even fairy tales revolve around theme. Nothing preachy. Just a subtle point to be made. I confess I'm not one to plan everything out before my first draft. It's usually the characters, and the story they tell, who define the theme at some point. And that often necessitates a re-write in later drafts.

I know, for myself, and for the members of the Readers' Group which I lead, we want to be challenged; to be made to think 'how would I react?' Or: 'Oooh, this is something new; never thought about that before.' Isn't that what makes writers like Jodi Picoult so popular?

We're on the same page here Mel. Everything you've said about theme etc is what I've said in the article. I use the word 'message'in inverted commas because that is the word that is often used in other discussions I've read about whether we should or shouldn't. OK I haven't put inverted commas in the title, I'll edit that in. But otherwise I'm not sure why people are confused. I refer to theme/message/something you want to say at different times in the article. Surely it's clear enough. But hey, perhaps not. Perhaps I've failed to communicate my 'message'. Now that's ironic ;)

ReplyDeleteNot at all Fiona :D You were very clear and, as you say, we're 'on the same page'. But having read what people have said elsewhere online, I do think there is some confusion; even some distaste because they misinterpret the concept of a 'message'.

DeleteFolks, I wrote this article hoping to get past the old circular argument of whether we should or shouldn't have something to say about our beliefs in fiction (whether those beliefs are religious, social, political or anything else). I was hoping to make the point that all good stories have something to say so we shouldn't get hung up about it. What I was really hoping is that we could have a discussion about practical ways we can engage with that in our writing without being preachy/on the nose/overt etc. I have suggested three ways. There are many others we could talk about: eg using symbolism and metaphor, contrasting character arcs and so on. I'm sure you have many more examples you can share. Please do.

ReplyDeleteRe: your point 1. CS Lewis said that Aslan came bounding into his imagination and pulled the stories after him. I think that’s a great way to describe the writing process and how stories can geminate in a writer’s mind.

ReplyDeleteHis friend JRR Tolkien couldn’t stand Narnia (which I've always felt was a great pity) and one of his reasons was that the Christian allegory stuff was too ‘on the nose’. My atheist friends growl about it too, especially The Last Battle. (I love The Last Battle, but then I would!) Ironically, I growl in the same way about Philip Pullman’s overly preachy atheism – although I think Pullman has a terrific imagination, and I want to read his latest.

Going back to Tolkien, who was a cradle Catholic, he once described The Lord of the Rings as ‘a profoundly Catholic work’. This at first came as a surprise to me, a dyed-in-the-wool evangelical Protestant, but now I understand what he meant, and I agree with him. (He was using ‘Catholic’ to mean ‘Christian’, not in a sectarian way.) There is in Tolkien’s work a deep Catholic sensibility of the nature of evil, for example.

I must admit I found The Last Battle a bit heavy handed. As a Christian I enjoyed it, but I did think it foregrounded the spiritual far more than the other books did and as such would me off-putting to non-Christians who had enjoyed the earlier books. I suppose it goes to show that the 'preachometer' varies according to how much one already agrees with sentiments being put forward.

DeleteOne of my favourite stories of all time is Oscar Wilde's The Selfish Giant. My father read it to me when I was a child, and I use it when asked to speak to primary school pupils on the subject of how to write story: plot, theme, character etc.

ReplyDeleteThe theme is the 'winter of the heart' that arises from selfishness when the giant refuses to allow the children to play in his garden which, ever after, is devoid of flowers and blossom. The ending still brings tears to my eyes when the giant eventually realises his error and helps a small boy into a tree which then breaks into blossom. 'You have let me play in your garden,' says the boy, 'today you shall play in mine which is Paradise.'

Nothing preachy in that. And although the story is a fable for adults, not children, the little ones all understand the message very clearly. And applaud it.

I remember that story! Yes, that is a wonderful example of how to do it well. Just the mention of the word Paradise is all that's necessary because the groundwork of showing not telling has already been done. Lovely. Thanks for sharing that.

Delete