The Boundaries of Myth

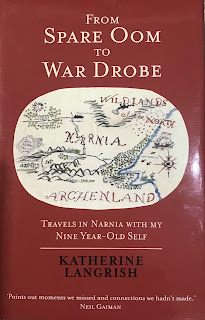

From Spare Oom to War Drobe by Katherine Langrish is a brilliant book, and for people interested in children’s writing or in C. S. Lewis it is a must.

Langrish, as a nine-year-old, adored the Narnia books and believed fervently in the real existence of Narnia. As an adult and a successful published writer of fantasy for children and young adults, she is still an enthusiast for the books, but with the more mature and critical appreciation of someone who has worked in the same genre and has researched and thought deeply about Lewis’s enterprise.

Her great achievement in FSOTWD is to retell the story of each Narnia book (in Lewis’s preferred order), without tediously rehashing them. Instead she makes her way lightly through the narrative, viewing it with both her nine-year-old eyes and her adult eyes, comparing their impressions, and showing us both the magic that lasted and the magic that tarnished, together with the reasons she ascribes for its success or failure.

The result is that we gain a tremendous insight into what works and what doesn’t work in trying to create a fairy-tale world, and also a better understanding of Lewis: what were his sources, where lay his particular strengths in creating a magical effect, and where he fell short. The book is valuable just as a catalogue of the sources that inspired Lewis. For example, Langrish brings out how much he owed to E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet: in fact, having read the latter, I think she slightly understates it. She reveals, fascinatingly, how he adapted motifs from a range of medieval and Renaissance sources, some now almost unknown.

Another very significant aspect of the Narnia books that she repeatedly underlines is how much Lewis confronts child readers with challengingly adult concepts. Sometimes it is simply the reality of blood and death, which are described quite graphically in several books. At other times it is philosophical perplexity: for example, the well-known confrontation between the Green Lady and Puddleglum in which the Platonic idea of the parable of the cave is used virtually in reverse. Langrish says that Lewis taught her to think in new and more advanced ways. Lewis indeed escaped from many of the tropes about writing for children. Langrish, as a child, relished the fact that girls were major, if not the main, protagonists, of the stories, and were portrayed as equally capable and practical as the boy characters.

She repeatedly shows how Lewis could write gripping, edge-of-the-seat narrative without which this kind of fiction is a nonstarter. She also brings out very well the especially spell-binding parts of the Narnia stories, in particular many episodes in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, one of her particular favourites, such as Lucy in the enchanter’s house on the Dufflepuds’ island, Lucy seeing the mer-girl, and near the end, the intense light, the sweet sea water, and the vertical wave up which Reepicheep’s coracle sweeps. She shows that Lewis definitely had the knack for that hardest of writerly skills, the creation of convincing myth or fairy-tale.

She shows us also the Narnian incidents which she now finds less compelling, even though at nine years old she enjoyed them, and some which she found hard going even as a child (for example the massively long flashback in the first half of Prince Caspian). These could be instructive to any of us who are trying to write for children. Ideally, we would wish to carry both children and older readers along with us. Most importantly, she discusses Lewis’s palpable failures. One is the trap that probably none of us would fall into these days, I hope (though Roald Dahl, considerably younger than Lewis, often falls — or perhaps dives headlong — into it): namely, social and racial stereotyping, as seen for example in the portrayal of Eustace Scrubbs’ parents and the Calormenes.

Much more significant in my view is how he handles the boundary between the mythical world and his Christian faith. ‘Of all the Narnia books The Last Battle is the one I liked least’, writes Langrish. I think her nine-year-old’s instinct was correct. Not that she rejected the whole story. She saw and still sees great merit in the story of the subversion of the innocent Narnians by Shift the Ape:

I well remember the anguished, helpless fury of reading all this when I was nine. But you know what? While writing this book I lived through the same rage. I recognised it: the horror and helplessness and bewilderment of living in a society broken down, divided and in conflict, with a fatuous, self-serving caricature in charge, who broadcast lies and claimed them as truths and called upon powers of darkness and violence. Here is a parable with relevance for our times. Tash walks through our world too.

The real trouble, for Langrish at nine and now, begins with the destruction of Narnia. In nearly the whole of the Narnia sequence, Lewis is scrupulous to keep the Christian story out of the fictional story: there are echoes and reflections which make Narnia powerful and compelling, while the boundary is carefully maintained. But Lewis was a very enthusiastic apologist, and eventually his zeal gets the better of him. The boundary is transgressed at the very end of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, but not disastrously. At the end of The Last Battle, however, there’s a major transgression against the integrity of the mythical world.

The whole magic and mystique of a ‘Narnia’ is that it’s an alternative world that you might accidentally fall into at any time. To have it wound up, destroyed, violates this essential fictional canon. Worse than that, the winding-up is presented not only as actually a jolly good thing, but as a good thing in Christian terms. The protagonists all die and enter a Narnian paradise, except for Susan, who is eternally lost, and nobody seems to care. This offended Langrish as a child and I think rightly. She was indignant and unconvinced. Christian writers may nod with approval at the ending because it portrays our beliefs so nicely, but I think that it succeeds neither as mythopoeia nor as apologetics.

For me, the saddest sentence of the book comes near the end of Langrish’s Afterword, where she outlines what happened to ‘the grumpy, passionate, imaginative little girl that used to be me’. She says ‘I remained a practising Christian for many years, but in the end — with relief as well as regret, regret as well as relief — I stopped believing in God.’

Adding my recommendations : a book well worth reading.

ReplyDeleteSounds interesting - the book I'd have written if I'd been more academic! I wrote about Narnia for my MA dissertation, but then lost the will to live when I thought about further academia... Sad about the writer's loss of faith!

ReplyDeleteI always enjoy your posts -informative and thoughtful.

ReplyDeleteThis is absolutely fascinating! I am going to buy the book right now. Also very sad to hear about the writer's loss of faith

ReplyDeleteQuite absorbing!

ReplyDelete